Today we are obsessed with fantasy, from Lord of the Rings to Harry Potter and Game of Thrones. We enjoy imagining these magical worlds where people can tap into ancient and mysterious powers, achieving things far more wonderful than in our mundane lives.

I do not need to recall here that the heritage of fantasy literature lies in medieval mythology. We know where Tolkien drew his inspiration and what followed. What I do want to consider, briefly, is both a similarity but a crucial difference in the fantasy world and the history on which it draws:

Both had magic, and yet in only one of them is it real.

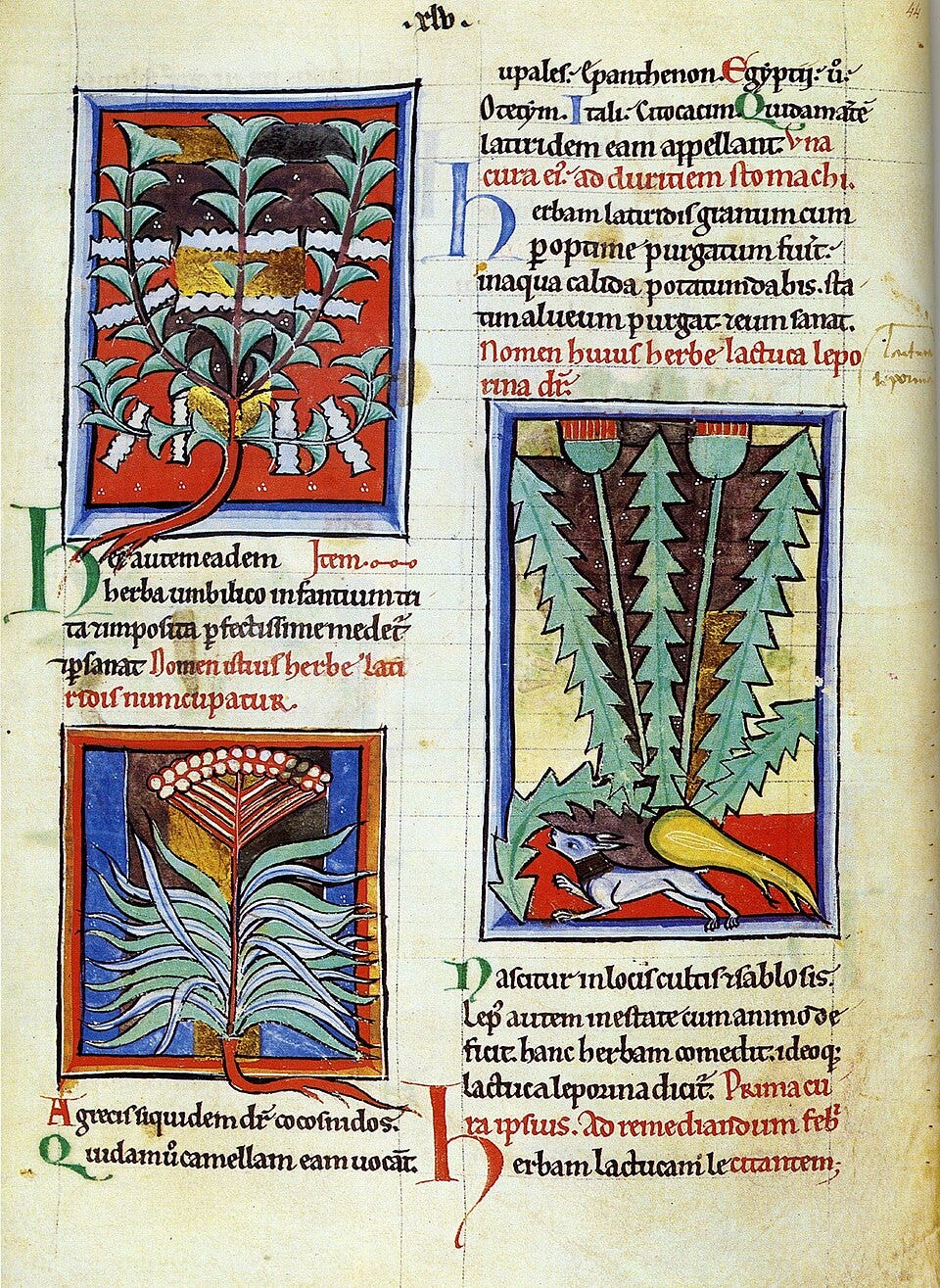

Consider this Old English herbal text:

‘Wið næddran slite genim þās ylcan wyrte þe we ‘ebulum’ nemdun, ǣr þām ðe þu hy forceorfe health hy on þīnre handa & cweð þrīwa nigon siþān: ‘omnes mala bestias canto’ þat ys þonne on ūre geþēode ‘Besing & ofercum ealle yfele wild-dēor’

‘Against adder’s bite, take this plant, which we named ‘ebulum’, (and) before you use it, hold it in your hand and say thrice nine times: ‘Omnes mala bestias canto’, that is, in our tongue: ‘Enchant and vanquish all evil beasts.’- Extract and translation from Bill Griffiths

This extract from an Old English herbal text (like these) recommended using wallwort to prevent the poison from the adder taking hold, but it is not the herbology I am interested in; it is the magic. Chants and charms such as these are the kinds of things we might see or read about in fantasy stories, but for the ancient and medieval worlds (though no doubt many modern ones too) they were real. This was everyday, practical magic, but coached in grandiose terms. They are fantastical in and of themselves.

Imagine you were the person on the receiving end of the charm. You are a peasant in 10th century England, sheltering in a rain-battered thatched house and groaning in pain. The adder’s poison is crawling its way through your body and you beg for relief. Above you hunches a man of the cloth, working up a herbal concoction. As the thunder cracks he shouts his divine command and drips it onto your wound. You continue to wince in pain throughout the night, but as the sun rises you feel healed. Did God grace you with his favour? Who knows, but the priest certainly claims that He did.

In a fantasy setting the scene would be far less grandiose. The adder bites you; you drink a potion; and you would be on your way. In the real world, for that medieval person, the reality is unknowable. Science can not yet explain it.

Before I make more of a point on this, lets consider another example: the final lines of a charm for combating a shooting or stabbing pain:

‘gif hit wǣre ēsa gescot oððe hit wǣre ylfa gescot

gif hit wǣre hægtessen gescot nū ic wille ðīn helpan

þis ðē tō bōte ēsa gescotes ðis ðē tō bōte ylfa gescotes

ðis ðē tō bōte hægtessan gescotes ic ðīn wille helpan

flēo þǣr on fyrgenhǣfde

hāl westū helpe ðīn drihten

nim þonne þæt seax ādō on wǣtan.’

‘If it was the shot/pain of ēse or it was the shot/pain of ælfe

or it was the shot/pain of hægtessan, now I want to help you.

This for you as a remedy for the shot/pain of ēse; this for you as a remedy for the shot/pain of ælfe,

this for you as a remedy for the shot/pain of hægtessan; I will help you.

Fly around there on the mountain top.

Be healthy, may the Lord help you.

Then take the knife; put it in (the) liquid.’

'Ēse,' 'ælfe,' and ‘hægtessan.’ Known to us as ‘god’ (specifically Germanic), ‘elf,’ and ‘seeress.’ The first charm warded against a beast of this world. This charm, on the other hand, tackles beasts of another world entirely (remember that elves started as mischievous characters, rather than later enlightened ones). Larger-than-life supernatural beings, and yet so interested in mundane mortal life that they would spend their time inflicting minor wounds on them. It is the mundane made fantastical by calling on a world a plan above that of normal people.

Drawing on supernatural explanations also has a function: it explains the unknown (Cameron 2014: 310). In the fantasy setting, there is no unknown. Magic is codified and understood. Elves walk amongst men, and gods make their presence known and even talk to mortals. King Æthelbert (d. 616) feared the missionaries who came to convert him would harm him with magical spells (Kelley 2014: 15). Did he fear the spells because he knew they were a possible threat, or because he had no way of knowing? In folk mythology humans fear the evil spirit in the woods. In fantasy settings, the adventurer slays it and turns everything back to normal.

Let us take a look at one final extract: a charm to prevent a swarm of bees from leaving the hives from where you extract their honey. I am going to quote this one in full as I love it so much.

‘Wið ymbe nim eorþan, ofer-weorp mid þīnre swīþran handa under þīnum swīþran fēt, and cwet:

“Fō ic under fōt, funde ic hit. Hwæt, eorðe mæg wið ealra wihta gehwilce and wið andan and wið ǣminde and wið þā micelan mannes tungan.”And wiððon forweaorp ofer grēot, þonne hī swirman, and cweð:

“Sitte gē, sīge-wīf, sīgað tō eorþan! Nǣfre gēwilde tō wuda flēogan. Bēo gē swā gemindige mīnes gōdes, swā bið manna gehwilc mētes and eþeles.”’‘Against bees, take earth, throw it with your stronger hand under your right foot and say:

“I put it under my foot, I found it. Lo! Earth can work against all evil beings and against malice and against the powerful person’s tongue.”And then throw over them the soil, when they swarm, and say:

“Settle ye, war-sives, sink to the earth! Never be wild and fly to the woods. Be mindful of my benefit, as are men of food and home.”

- Extract and translation (with some slight edits) also from Bill Griffiths

This charm is unique to the others in that it allows the user to actively shape the world of beasts of supernatural forces, rather than simply being protected from them. What I enjoy about this extra is the poetic grandeur of the whole affair. Bees are described as “war-wives,” as though we are dealing with a scene from Norse mythology.

What unites all of these charms, though? Well, in our real world, the magic we come up with to solve our problems tells us something about our human beliefs, fears, and values. They represent our need to tangle with forces that feel out of our control. The spirits and demons out to get us represent something about us, rather than just being real dangers. The spells we devise to manipulate our world represents our endless tussle with nature. Those who successfully wield magic our revered as gods, saints, and folk heroes. In fantasy, only the most powerful of magic users deserve such status. The rest are ten a penny.

Do we look at chemists as we do alchemists in movies? Do we watch in wonder as computer scientists teach thin slices of rocks how to think, as we read in wonder at a dwarven mechanist doing the same thing? We did, once. The lines between scientist and magician were once blurred, each believing they had legitimate command over natural forces. But not anymore.

‘Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic,’ as Arthur C. Clarke said. What he missed was: ‘until we start using it to do online shopping.’ We might not be able to explain it in detail, but it is known and knowable. It is therefore largely boring. Only the mysteries on the very verges of our knowledge remain exciting to the majority.

In fact, when we read or watch the magic of fantasy settings, our sense of disbelief and excitement might come from the fact that the machinations of that world are unknowable. They are the preserve of the artist. This is why I dislike fantasy books that describe their magic-systems in depth. Its also why I sometimes regret deep-diving into lore, only for it to become too familiar to be exciting.

Where am I going with this? I am unsure. This has turned into a collection of musings, or a drawn out question. That is: has something been lost in turning a world of unknowable and irrational magic into a knowable and rational one? Or: what replaces belief and superstition when magic becomes a real and normal part of life?